A common structure in OLTP systems is a parent-child relationship with Object and ObjectParent tables creating a recursive structure. This is easily represented as a Warehouse dimension table, usually flattened out but occasionally left as native Parent-Child if required.

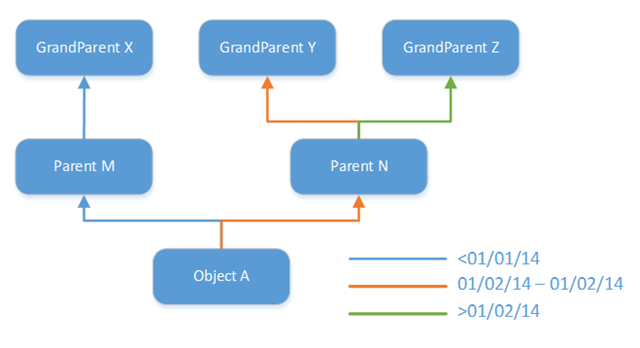

I recently encountered an issue where the client not only required a flexible, dynamic parent-child dimension but also required it to be slowly changing. Each fact record joining to the dimension, at any granularity, had to be aware of its hierarchical context at that point in time, despite there only being one source record for dimension object. We end up with something like this:

Throughout the course of the engagement I implemented two different models for this as requirements changed, I’ll detail the solutions in part 2 of this post.

If you’re not familiar with Slowly Changing Dimensions, namely Type 2 SCD, I put together a quick introduction in a blog post here to bring you up to speed.

So how do you slowly change a Parent-Child relationship?

Since we have source records for each node in our hierarchy, it makes sense to keep this structure. However, over time that same node can fit into the hierarchy in different places, changing parent records, gaining/losing children or even moving levels.

We therefore need to differentiate between the different hierarchal contexts of node. As with other SCD implementations, we give each historical version a surrogate key, so we can accurately identify the node in the relevant context.

Parent-Child makes this tricky however – if we just created historical versions when the individual nodes changed, records joining in at lower granularities would not know which historical version to use. We therefore need to amend child nodes to point to the new surrogate keys. This, in turn, means we have to create new references to those nodes, and so on down the hierarchy.

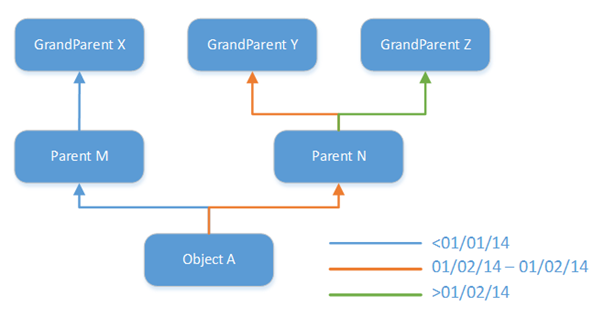

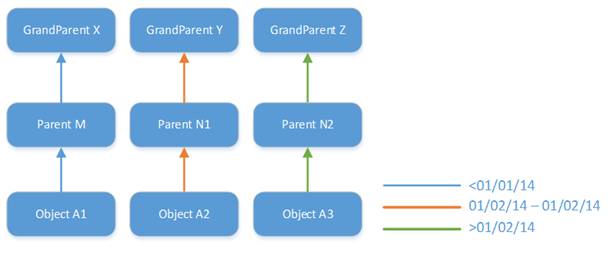

Essentially, anytime a node in the hierarchy changes, we need to create new historical versions for all descendants of that node. Our original structure, using this method, would now look like this:

You can see that when Parent N’s own parent changed, we had to propagate that change to Object A to ensure our lowest granularity object has a key for each temporal version of the structure.

We can now use this structure with a fact table – we know that a fact record occurring on 10/02/14, for example, would aggregate up the orange-marked path through A2 > N1 > Y.

That’s the key point to implementing SCD for Parent-Child structures. If any changes occur, anywhere in the hierarchy, all descendants will need a new type 2 record created. By using Type 2 SCD, each object is referencing the surrogate key of its parent, not the business key, this way every join in the structure is based upon a specific historical version of that record and thus historical context is implied by the foreign key relationships.

Whilst complex in theory, once implemented your fact > dimension relationship is very simple. Your fact record has a single foreign key which holds the full historical context of that record.

In the next post, I’ll discuss a couple of techniques for implementing the above transformation inside a standard ETL structure.

Using Copilot Studio to Develop a HR Policy Bot

The next addition to Microsoft’s generative AI and large language model tools is Microsoft Copilot

Apr

Pretty Power BI – Adding GIFs

Good UX design is critical in enabling stakeholders to maximise the key insight that they

Apr

Pareto Charts in Power BI and the DAX behind them

The Pareto principle, commonly referred to as the 80/20 rule, is a concept of prioritisation.

Apr

Databricks: Cluster Configuration

Databricks, a cloud-based platform for data engineering, offers several tools that can be used to

Apr

AI Assistance in Microsoft Fabric

The exponential growth of Large Language Models (LLMs) couples with Microsoft’s close partnership with OpenAI

Apr

10 reasons why it’s worth the effort to understand the value of your data

“If leaders really want to create a data driven culture, the journey starts with them!

Apr

Content Safety in Azure AI Studio

Azure AI Content Safety is a solution designed to identify harmful content, whether generated by

Apr

Model Benchmarks in Azure AI Studio

In the constantly changing field of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), choosing the

Apr